If Family Feud polled a random sampling of 100 authors, poets, and lyric writers at a convention, and asked them why they put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard), I bet I can tell you the number one answer: “I can’t not write.” This is ironic because even Bart Simpson knows, “I won’t not use no double negatives.” Clearly stating, “I’m compelled to write,” in the affirmative would be the proper English equivalent, yet it lacks the je ne sais quoi to convey the conviction delivered through deliberate use of the double negative. It’s conviction that allows a person who writes to finally consider him or herself a writer, and it’s almost as if “I can’t not write” is the secret password that allows each of us into that exclusive club.

If Family Feud polled a random sampling of 100 authors, poets, and lyric writers at a convention, and asked them why they put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard), I bet I can tell you the number one answer: “I can’t not write.” This is ironic because even Bart Simpson knows, “I won’t not use no double negatives.” Clearly stating, “I’m compelled to write,” in the affirmative would be the proper English equivalent, yet it lacks the je ne sais quoi to convey the conviction delivered through deliberate use of the double negative. It’s conviction that allows a person who writes to finally consider him or herself a writer, and it’s almost as if “I can’t not write” is the secret password that allows each of us into that exclusive club.

Now that you know our password and are inside our hallowed grounds—the inner circle sanctuary of writers self-possessed to create with words—let me explain how I arrived here. I have proclaimed our writing sanctuary to be hallowed grounds, but more often than not, the inner landscape of wordsmiths is a personal hell that each of us tries to decorate and make more palatable. I am no exception. I became a writer because tragedy destroyed the world that I knew and loved, and for many years I failed to adapt to my new reality.

On July 17th, 1996 my fiancée Susanne left New York for Paris onboard TWA Flight 800. All 230 passengers and crew blew up off the south shore of Long Island. Nobody on that Boeing 747 survived. I was thirty years old, the love of my life suddenly disappeared, and my airline was plunged into group depression. At the time I was a pilot, and had not even considered becoming a writer. Homeowner, husband, and father—these were the titles I was readying myself to accept as my thirties unfolded, and then they all suddenly disappeared in a giant fireball at 13,760 Feet.

On July 17th, 1996 my fiancée Susanne left New York for Paris onboard TWA Flight 800. All 230 passengers and crew blew up off the south shore of Long Island. Nobody on that Boeing 747 survived. I was thirty years old, the love of my life suddenly disappeared, and my airline was plunged into group depression. At the time I was a pilot, and had not even considered becoming a writer. Homeowner, husband, and father—these were the titles I was readying myself to accept as my thirties unfolded, and then they all suddenly disappeared in a giant fireball at 13,760 Feet.

Ten years later I turned forty, and my closest two people came to visit. My father and my best friend Warren staged a small intervention. They were concerned that I wasn’t moving on with my life. In my defense, I had biked across the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary; trekked Nepal; and traveled solo around the world. I continued to fly for my airline, and I had finally bought a house on my own. I tried showing them how functional I was, but they didn’t buy into my bullshit. They rubbed my nose in my catch-and-release relationships, my live-each-day as-if-it’s-my-last celebrations, and the general detachment with which I conducted my life. It took these extreme adventures, large purchases, and casual affairs for me to find any kind of temporary happiness. Dad and Warren challenged me to find a way to open my heart and begin really living again. They didn’t know how I would do it, I didn’t have any suggestions to offer, but I accepted their concern and I began chewing on their request.

Shortly thereafter, I was working out in a hotel gym while on a layover when the lyrics to my first song “From a Long Way Away” began appearing in my head:

From a long way away

Everything still looks OK

I still go to work

Well, almost everyday

I put my tongue on the roof of my mouth

It keeps me from saying what I have to say

It finally occurred to me that I really was faking smiles and pretending to be happy.

I put my tongue on the roof of my mouth

It makes me look like I’m smiling

Day after day

Day after day

In my early days after losing Susanne, my airline had appointed a counselor for my personal well being. Probably while noticing my resistance, she told me: emotions I bury, I bury alive. As I started writing down my initial lyrics, it occurred to me that I’d been physically all the way around the planet, but I hadn’t moved an inch emotionally.

I get around but have no place to be

And you can’t see anything wrong

Just by looking at me

Ten years later, after that intervention, I began to dig my buried emotions back out—through creative writing. These lyrics spawned an aspiring songwriter character in what became my first novel, and I began working through my own survivor’s guilt and grief by melding prose with original companion songs. There is always some truth in fiction, and I was bleeding my own pain onto the page, while trying to balance it with music and adventure. Fifteen drafts finally produced a novel I became proud enough to release to the world. Because of its original-song infusion, I turned Pushing Leaves Towards the Sun into a 36-episode podcast audiobook that I still give away for free through iTunes. It’s my first work, and it’s free in this format for three reasons. First, it’s an always-available companion for anyone suffering with their own survivor’s guilt and grief. Second, it introduces potential readers to my writing and song-infusion style. And third, my blend of books with their own internal soundtrack is better experienced through audio than described in print.

Ten years later, after that intervention, I began to dig my buried emotions back out—through creative writing. These lyrics spawned an aspiring songwriter character in what became my first novel, and I began working through my own survivor’s guilt and grief by melding prose with original companion songs. There is always some truth in fiction, and I was bleeding my own pain onto the page, while trying to balance it with music and adventure. Fifteen drafts finally produced a novel I became proud enough to release to the world. Because of its original-song infusion, I turned Pushing Leaves Towards the Sun into a 36-episode podcast audiobook that I still give away for free through iTunes. It’s my first work, and it’s free in this format for three reasons. First, it’s an always-available companion for anyone suffering with their own survivor’s guilt and grief. Second, it introduces potential readers to my writing and song-infusion style. And third, my blend of books with their own internal soundtrack is better experienced through audio than described in print.

My early readers loved my first novel, but all seemed to realize I was avoiding my real life experience by putting fictional characters through my pain. Even when I applied for creative writing grad school, with the intention of completing the second novel I’d started, my readers clamored for a memoir about TWA Flight 800. When the university’s director accepted me for nonfiction, I told him only famous people and narcissists wrote memoirs, and I was neither the former, nor wanted to become the latter. He corrected me, and explained that people with compelling stories write memoirs. I agreed to give it a try, and soon Airways magazine began publishing my new memoir chapters as stand-alone articles.

Let me wrap up with a word for aspiring writers and authors. I still earn a living as a pilot, and I consider the money I receive as a writer to be a stipend, even though my twenty-third Airways article just appeared in the November 2014 issue. Becoming a published author is merely a milestone along a writer’s journey. It’s significant, but what makes us tell our stories. Do golfers need to play on the PGA tour to consider themselves golfers? Is a high school quarterback any less of a football player than an NFL pro lineman? We are who we believe we are. I was excited that Airways began publishing my work, but I’d considered myself a writer long before I entered creative writing grad school, or the first of a dozen journals accepted my writing. If you wonder about your own literary motivation, just ask yourself if you are a writer, and then listen for your inner voice to handle this question for you. Did it reply, “I can’t not?” Because by now, I hope you understand that you ARE a writer if you can’t not write.

**** **** **** **** **** **** **** **** **** ****

note: The song “From a Long Way Away (Lindy’s Theme)” can be heard here:

note: The song “From a Long Way Away (Lindy’s Theme)” can be heard here:

– Performed by Kim Smith, J Starck, Bill Johnson, & Dave Morgan

Lyrics & mp3 – plus Artist links /

or here:

http://marklberry.com/pushingleaves/from-a-long-way-away/

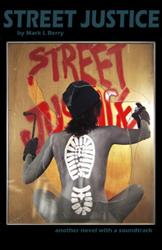

This blog was inspired by an e-mail I received from national training company www.webucator.com‘s Marketing Manager Bob Clary. His November marketing effort is inspired by NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) and he is reaching out to authors to find out what makes us tick. I am proud to say that I completed the rough draft of my second novel (and third overall book) Street Justice during NaNoWriMo several years ago. I plan to polish and publish it in 2015. There are still a few test copies available if any serious readers want to provide me with honest feedback before my final revision.

capnaux says

Excellent post, Mark. Very well said! We can’t not heal, if we expect to live. The more you open up about your incredibly painful journey, the more it helps the rest of us get through that which we all must inevitably face in our lives.

Thank you for your words!

Karlene says

This is a wonderful post. And perfect timing. More on the beautiful story and writing can be found HERE: http://karlenepetitt.blogspot.com/2014/11/sometimes-road-is-long.html

David says

Fascinating insight Mark. Writing can be so therapeutic at times, even if you are the only one who gets it.