Sometimes the planets do align. Just as my Blogging in Formation group was deciding on “Solo Flight” as our April theme, I received an e-mail from Matt Guthmiller, an MIT student promoting his upcoming around-the-world solo flight. Matt plans to fly a Beechcraft A36 Bonanza 28,000 miles this summer. If successful, he will become the youngest person to accomplish this lap around the globe.

On a personal level, I applaud Matt’s mission as a great adventure, and I wish him a safe journey. I asked him his age (19) and his level of aviation experience (Commercial Pilot -Single-Engine) before agreeing to promote his plan. I recall another record setter a few years ago that ended in tragedy. Fatal misfortune found the seven-year-old who was attempting to become the youngest ‘pilot’ to fly across the country–except U.S. citizens can’t even become pilots until they can legally obtain a combination medical and student pilot certificate (age 16). I wanted to be sure that Matt’s record-breaking ambitions were not overriding his caution. I think less about the world record, and more about Matt recording his trip around the world to share with others–inspiring big goals, careful planning, and hard work. I hope he is able to effectively share his journey through photos and description, not only about what he sees along the way, but how it changes his view of the world once he knows first hand its full circumference.

You can read more about Matt’s upcoming solo flight at:

http://www.limitless-horizons.org

In honor of Matt’s upcoming grandiose solo journey, I share with you my first solo flight. It was just three take-offs and landing at Daytona Beach Regional airport back in 1983, but it marked my initiation into the pilot ranks.

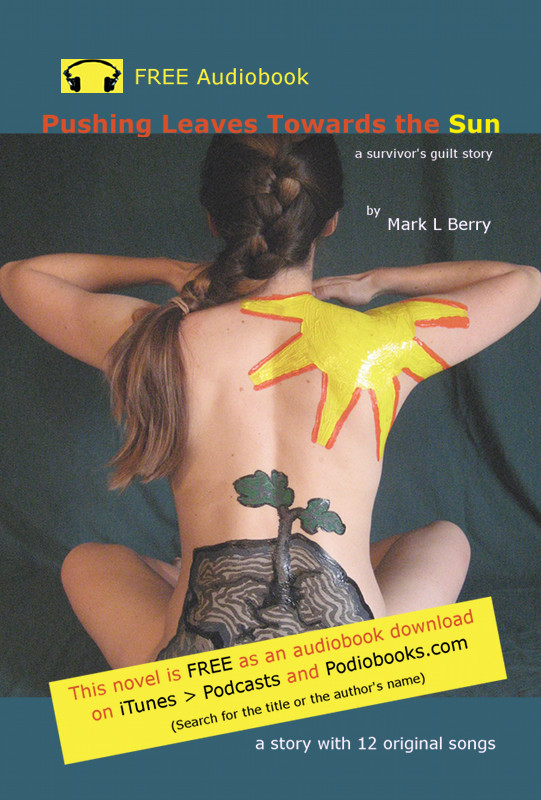

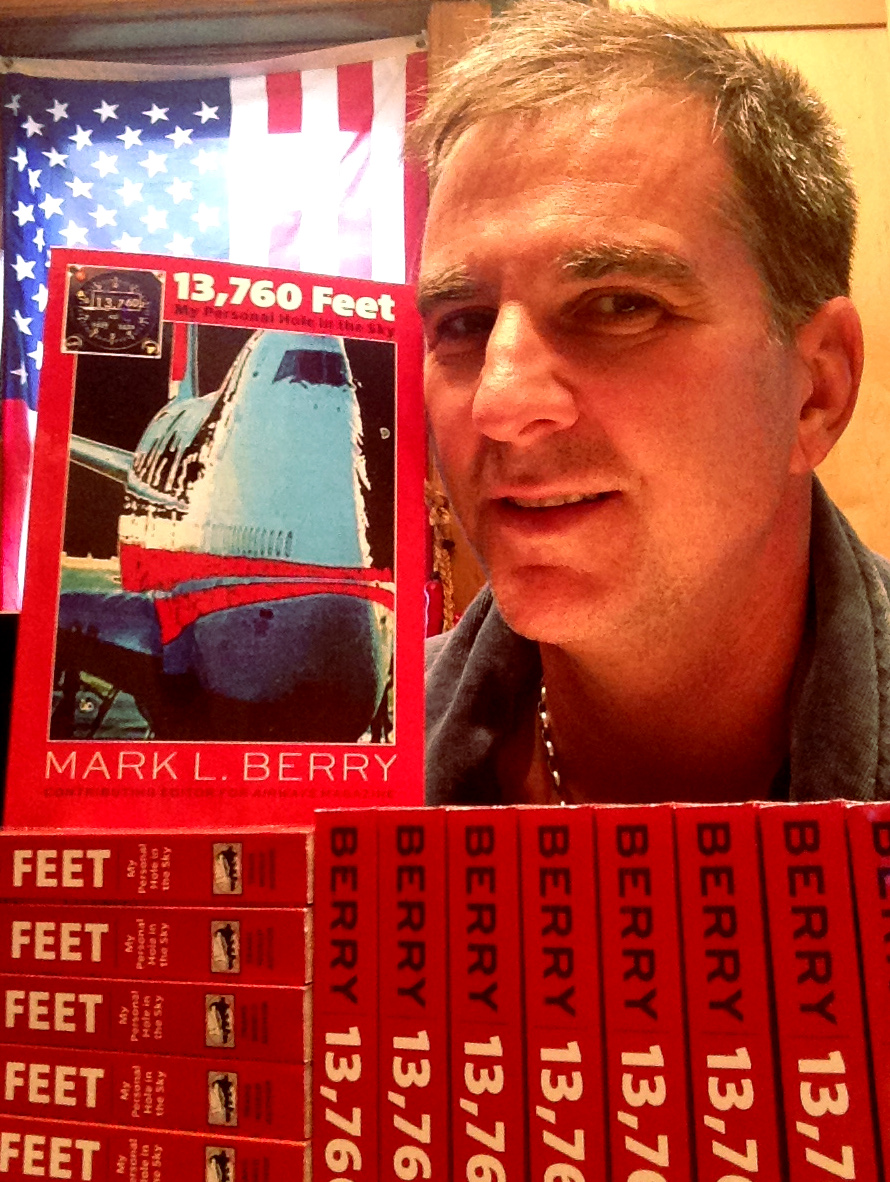

This is an excerpt from my article “25 Years Since ERAU” that appeared in ERAU EaglesNEST, and also ended up in my my memoir 13,760 Feet–My Personal Hole in the Sky as part of Chapter 8.

“My First Solo” by Mark L Berry

(the italicized paragraphs are lyrics for the infused companion song “My First Solo” performed by Billy Sea)

My First Solo (companion song)

Words by Mark L Berry & Music by Billy Sea

Performed by Billy Sea

One of my childhood goals was professional baseball; I was born with the initials for it after all: MLB. At eight, I was a starter in the nine- and ten-year-old league and I had a mean fastball with a natural rising screwball action. I spent plenty of time pitching to those backstops that Stuart and I raced around, and tried to keep batters from knocking the ball over the perimeter fence and into the graveyard beyond. As a lefty, I could throw it inside the plate to right-handed batters and it would ease over the inside corner. Every strike appeared as a brush-back pitch. When I could control it, that is, and therein lied the problem. I threw harder than my peers, and some of them had the bruises to prove it. My nickname was Beanball Berry.

One of my childhood goals was professional baseball; I was born with the initials for it after all: MLB. At eight, I was a starter in the nine- and ten-year-old league and I had a mean fastball with a natural rising screwball action. I spent plenty of time pitching to those backstops that Stuart and I raced around, and tried to keep batters from knocking the ball over the perimeter fence and into the graveyard beyond. As a lefty, I could throw it inside the plate to right-handed batters and it would ease over the inside corner. Every strike appeared as a brush-back pitch. When I could control it, that is, and therein lied the problem. I threw harder than my peers, and some of them had the bruises to prove it. My nickname was Beanball Berry.

I should have stuck with pitching—lefties are always in high demand in the big leagues—but I also loved to bat. Pitchers didn’t play every game unless they were also awarded a second position, and therefore didn’t spend as much time at the plate. Pitchers typically bat ninth, and I wanted to bat in the front of the lineup. Instead of improving my throwing accuracy, I focused on my hitting. By the time I moved up to the Junior Babe Ruth League at age thirteen, my coach moved me over to first base so I could stay in the line-up every game. I accepted my coach’s wisdom and left pitching to my teammates who were learning to throw fancy pitches like curves, change-ups, and sliders. My pitching reputation didn’t fully go away after I forfeited the mound, though. At my ten-year high-school reunion, I thought Will Wilson was approaching me to shake hands and say hello. Instead he said, “Hey Beanball, in fourth grade you hit me in the back with your uncontrollable fastball. I still remember it.”

“That’s Captain Beanball to you.” It was good to be remembered, but not as the kid with the wild arm. He didn’t need to know that I was still merely a first officer at my airline at the time. Reunions are great for glorious self-declarations of success.

As I was growing up, the baseball funnel grew tighter as all three of my town’s junior high school teams graduated into a single high school. Being good wasn’t good enough. I didn’t make Greenwich High’s roster. My major-league baseball dreams were crushed about the time I was learning to drive.

High school became my soul-searching time, and like almost every other kid, I had to face the future as Mom and Dad made plans to kick me out of their nest. That’s when I asked for flying lessons at a nearby airport in Westchester, New York.

After an introduction and a handshake, Glenn Larson became my first flight instructor. He asked me, “Shall we check the weather?” as he walked me over to an area set up as a multi-use office. Lots of machines were buzzing and humming. I remember watching weather reports spit out on tickertape, and instructor Larson read official-sounding words from the gibberish shorthand. A glass door beyond the flight planning area revealed a ramp filled with single-engine Piper Cherokee airplanes. Behind them were a multitude of colored lights and a maze of pavement. As we walked to tail number 1945-Hotel that would be our aircraft for the next six-tenths of an hour, Instructor Larson handed me a small clear cup and taught me how to sump the wing tanks free of water. AvGas spilled on my hands and the flying bug soaked into my soul. I could smell my future in the sky as I held the cup up to my face to see the separation of AvGas and the little bit of water I’d drained from the tank. We opened the cowling and checked the oil level, verified the tire inflation and remaining tread, tugged on the flight controls, and everything I touched on the plane felt like first-kiss excitement.

On this introductory flight, in addition to the four fundamentals—climbs, descents, straight and level flight, and turns—we flew over my house for a new aerial perspective of familiar surroundings. Trees obscured it, but we saw the neighborhood churches and schools, including North Street Elementary. I was awed by the whole experience until Instructor Larson put me back to work learning to operate the aircraft. My logbook includes radio communication in my initial entry. Communicating with New York’s extensive air traffic control system was something I’d have to learn by doing. He taught me to unkey the microphone if I was going to say uh. Better to let someone else talk than announce to the world that I was standing on my tongue.

After Instructor Larson landed with me following through on the flight controls—we each had our own interconnected control yoke and rudder pedals, but we shared a single throttle between us—I tried taxiing the airplane back to the ramp while he kept our wheels on the pavement. Mom picked me up—I was old enough to take flying lessons but still only possessed a learner’s driving permit. It was obvious to her that I was onboard with this new activity, so she bought me a logbook for Instructor Larson to sign and a primary flight book that I still recommend as a first read for flight students—William Kershner’s Student Pilot Flight Manual.

My enthusiasm earned me a trip to Daytona Beach to visit Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University with my dad, my first and only campus tour, and I decided on the spot that’s where I wanted to go to school. Afterward, we extended our trip to the Florida Keys for the scuba diving mini-lobster season, and flew on Provincetown Boston Airlines—whose single pilot delivered us to Marathon Key. I won the golden-ticket: I was able to ride in the co-pilot’s seat. I wore a set of heavy headphones that completely covered my ears and tried to make sense of the radio communication. I wondered what all the cockpit buttons and knobs did, much as many of my passengers wonder about them today.

I didn’t have any clue about the job market back then, but my dad had some understanding because he was a businessman. With no formal aviation training yet, he was already studying the industry from a financial viewpoint to see if learning to fly would offer me an opportunity to obtain a reasonable return on the required educational investment. As I returned the borrowed headset to our pilot, and stepped out onto the tarmac for the walk into the terminal, my dad grabbed our bags and asked me a serious question. “If flying Cessna 402s around the Keys is as far as you advance in your career, will you be satisfied?”

I was post-airborne euphoric. The flight up front was better than any home run I’d ever hit. For me, flying was just about the flying. Earning a living was still an abstract idea. I was still in high school and hadn’t paid rent or any bills. I think Dad was trying to prepare me in case my flying career got stuck like my baseball ambitions. My view was idealistic and I said, “Hell yeah!” That was good enough for Dad.

Airplanes fascinated me as a small child. Now I sized this metallic-winged creature up with a serious gaze, as if it was an opposing pitcher and I was a fan suddenly invited to don a uniform and step up to the plate to face it. I’d turned the corner and found a new, more obtainable career goal than baseball, although Embry-Riddle accepted me as both a flight student and a baseball player.

As high school ended, I couldn’t wait to learn how to fly. Six days after my high-school graduation, I planned to drive my loaded my car to Daytona Beach in order to start college with summer school. My coach was crushed because my senior Babe Ruth baseball league was still only midseason through our schedule. I was batting over six hundred after nine games against my high school’s pitchers, who were spread around the league for additional playing opportunities.

My parents miscalculated their annual vacation and left me as the man of the house as high school ended. I walked across the stage in my cap and gown and then threw a high school graduation bash for three hundred friends; all the while my folks were sailing in Greece. Piss-poor planning on my parents’ part, and I was long gone by their return.

The first letter I found in my new university mailbox was from Mom and it began, “Dear Mark, why is our lawn growing flip tops this year?” This was before the tabs on beer and soda stayed attached to the cans after opening, and I hadn’t stuck around town long enough to collect those shiny little discards.

After Dad cleaned up my mess, and made me feel guilty because our dog cut his paws on the sharp aluminum hidden in the grass, he decided to check out what it was that I saw from the cockpit. He bought an old Piper Cherokee 160B—the same aircraft type used during my first flights at Westchester County airport—to take his lessons in during weekends. He was running a manufacturing business. It was the beginning of the computer age and his company was developing scuba diving computers back when they were big and clunky—the size of a paperback book with the weight of a softball. This began our friendly rivalry: who would earn his private pilot’s license first, and take the other one flying? The loser would have to buy clam chowder on Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and Block Island as we planned to make a cross-country chowder run during my next visit home.

Most of the family flying was shared only between Dad and me. My brother didn’t have any interest in aviation, although he recently surprised me by skydiving. Mom went with us once, but screamed louder than she did at Yankee games. Her friends called her Pat, my dad called her Trish, and the stadium ushers often called her over to have a talk about her unbridled enthusiasm. She was a true fan and always at the verge of being ejected. She had the world’s longest brown ponytail that she pulled through the back of an adjustable baseball cap, and she cheered and jeered like nobody I’ve ever met. She loved attending baseball games—both the pros and mine. Maybe that’s why a career on the mound seemed so appealing during my impressionable years. Mom’s attention was very focused at the games.

One afternoon at college, my scheduled training flight was rained out. That’s something that flying airplanes and playing baseball share; they’re both subject to delay and cancellation due to foul weather. As I returned to my dorm, I was doused with water from all directions. The parking lot flooded during extreme afternoon thundershowers, and the battle of the dorms was happening with wastebaskets and water balloons. It was all kinds of fun until my instructor showed up looking for me, and was also doused and soaked in the process. Instructor David Esser told me the rest of his afternoon flying was cancelled, but since I lived on campus we could go up when there was a break in the weather. “Awesome, just let me change.”

“No,” he said. “If I have to fly wet, so do you. And by the way, your friends are all crazy.”

“I know, isn’t it great?”

Off we went, to the small southern runway at Daytona Beach Regional Airport in a Cessna 172 Skyhawk—a bird we sarcastically called the mighty Chickenhawk, but we really revered it with affection. It has a high wing with diagonal support struts running down to fixed, not retractable, landing gear. Inside there is room for two pilots and two passengers behind a single engine in the nose that powers a two-bladed propeller. Our school’s aircraft are all painted white with light blue and a single dark gold stripe, and all of the registration tail numbers end in ER for Embry-Riddle—pronounced Echo Romeo in the phonetic alphabet over the radio.

Startin’ the engine

Instructor just watchin’

He’s just relaxin’

Lettin’ me try

To handle the throttle

The flaps and the radio

Rollin’ for take-off

He’s lettin’ me fly

Three times Instructor Esser and I went around the traffic pattern together and then he told me to pull over onto the local fixed base operator ramp—a facility for general aviation aircraft.

Three landings later

We pulled over

Under beautiful weather

And a clear blue sky

I was confused because Embry-Riddle had its own ramp where we parked our airplanes. He hopped out, but before he reclosed the door, he said, “Now go back out and do what we just did three more times. Remember, the airplane will be lighter without my weight in it, but you can handle it.” With that he closed me in that little cockpit, walked into the building attached to the hangar, and was gone.

I later learned that this was the old school method—the human version of being kicked out of the nest. No dwelling about soloing—I was just made to go out and do it without warning.

I was both scared and excited as I looked over at the empty seat beside me. I was hyper-aware now, and even noticed that Instructor Esser had courteously secured his seat belt and shoulder harness. I restarted the engine and read my checklist out loud. Releasing the brakes was the deciding moment. With just a nudge to the throttle, I was rolling and on my way on my own.

I’ll never forget

My first solo

Instructor hopped out

And away I go

I taxied out only to find the airport was just turned around. The wind had shifted and takeoffs and landings were now operating in the opposite direction. I briefly considered turning back to retrieve my instructor. Was I qualified to do other than what he’d specifically told me to do? The urge to solo took hold of me and I rationalized, I need to be flexible. Adapt, isn’t that what pilots do? I wondered what Instructor Esser thought when I taxied a direction other than expected. I don’t know what the aviation equivalent of Beanball is, but he was probably thinking it. Perhaps he was wondering what else he was qualified to do if the FAA ripped up his license. As a solo student, I was flying on his ticket.

I’ll never forget

My first solo

Up in the air

Up all alone

No one to ask

No one to talk to

No one to blame

My oh my

I was really flyin’

I was really tryin’

To keep from Diein’

Durin’ my first landin’

I was really sweatin’

No time for contemplatin’

Put it on the runway

On my first try

I wasn’t signed off for touch and goes—every landing had to be made to a full stop with a lengthy taxi back for another takeoff. Air traffic picked up as darkness approached and day-flight-only students returned from the local practice areas. It was a double Ray-Ban shade of dusk when I taxied back into the FBO ramp to pick up Instructor Esser. He was wired on iced Pepsi, his favorite vice, and was still holding a giant cup of it. I was wired too—I had just soloed! He sipped while letting me taxi back to the school’s ramp to park the plane. I tried to be smooth on the controls so he didn’t spill.

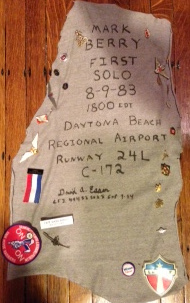

We went up to Instructor Esser’s desk and he grabbed a pair of scissors. Several other instructors and fellow students watched as he cut the back off my T-shirt, still wet from the water war and now also mixed with my sweat. I was initiated as a fledgling pilot in the true aviator’s tradition. He signed my now priceless shirttail with the airport name, runway, and date—8-9-83. First solo is the monumental milestone, even with so many more ahead. The shirttail was a trophy like none I’d ever earned before, because it marks the day I can forever look back, and recognize myself as a pilot. I sent it to my dad with thanks for his support. A few weeks later his arrived in the mail, and I hung his solo shirt up proudly in my dorm room. Coincidently, we were scheduled to solo on the same day, twelve hundred miles apart, and we were both rained out. My soaking wet instructor made up our flight right away, while it took my dad two more weeks to reschedule.

If you liked Chapter 8,

you can find Mark’s entire memoir 13,760 Feet–My Personal Hole in the Sky on Amazon.

Sometimes we are not polite, and anonymous blog posters throw verbal hand grenades at other peoples’ ideas; I approve all but the most vulgar posts on my blog in the interest of sharing different points of view. But others offer more constructive criticism—new clues or corrections why one theory or another doesn’t quite fit, and needs to be adjusted. I’m hoping my fellow aviator Ron will share his expertise on ELTs (emergency locator transmitters) and why he feels we would have found the aircraft already if it crashed on land or in the water. ELTs only send out a signal after the force of an impact triggers them. My buddy Warren asked me, in a not so friendly flabbergasted tone: “Why can the oxygen on an airplane even be turned off on an airplane?” And of course the answer is: it would need to be shut off periodically for maintenance or servicing. “But why in flight?” Well, the law-abiding majority of us find it difficult to imagine how someone would want to deliberately misuse a safety system. And I’m not saying that happened for sure on the Malaysia flight. But our collective speculation about the unknown allowed us to debate that idea, and now regulators and manufacturers might consider designing a system that can only be shut off on the ground. Will this make aviation safer? It might, or it might not. But my point is that our social media postings—our desperate attempt to make sense of a critical situation that has left us too few clues—can still be put to productive use. No theory is ridiculous if it brings about a positive change.

Sometimes we are not polite, and anonymous blog posters throw verbal hand grenades at other peoples’ ideas; I approve all but the most vulgar posts on my blog in the interest of sharing different points of view. But others offer more constructive criticism—new clues or corrections why one theory or another doesn’t quite fit, and needs to be adjusted. I’m hoping my fellow aviator Ron will share his expertise on ELTs (emergency locator transmitters) and why he feels we would have found the aircraft already if it crashed on land or in the water. ELTs only send out a signal after the force of an impact triggers them. My buddy Warren asked me, in a not so friendly flabbergasted tone: “Why can the oxygen on an airplane even be turned off on an airplane?” And of course the answer is: it would need to be shut off periodically for maintenance or servicing. “But why in flight?” Well, the law-abiding majority of us find it difficult to imagine how someone would want to deliberately misuse a safety system. And I’m not saying that happened for sure on the Malaysia flight. But our collective speculation about the unknown allowed us to debate that idea, and now regulators and manufacturers might consider designing a system that can only be shut off on the ground. Will this make aviation safer? It might, or it might not. But my point is that our social media postings—our desperate attempt to make sense of a critical situation that has left us too few clues—can still be put to productive use. No theory is ridiculous if it brings about a positive change.

So where does this leave us? In a heap of danger, that’s where. Until we actually KNOW what happened to MH370, we need to BE PREPARED for what can happen next. It seems that there is a lot of speculation and hindsight in the media, and not enough looking ahead. When that 777 re-appears on radar or a satellite display, there won’t be much time to think about what to do. Either the world’s military acts immediately, or terrorists have an opportunity to ratchet up their level of destruction to previously unimagined levels. This is not a time for wishful thinking; this is a time for preparation for immediate action. There as a Boeing 777 at large, and very possibly it is in flyable condition and in the hands of terrorists. Do we as a peace-loving people have the foresight and will to actively shoot down an airliner when it re-appears? It won’t take to the sky again with innocent intentions. That is my worst fear, and I wrote this hypothesis with the hope of preventing it from becoming reality. Maybe I’m wrong, but if I am right, can we afford to wait and see? At the bare minimum, we should be on high alert until that aircraft is found—either intact, or in pieces as a result of a tragedy other than this hijacking scenario.

So where does this leave us? In a heap of danger, that’s where. Until we actually KNOW what happened to MH370, we need to BE PREPARED for what can happen next. It seems that there is a lot of speculation and hindsight in the media, and not enough looking ahead. When that 777 re-appears on radar or a satellite display, there won’t be much time to think about what to do. Either the world’s military acts immediately, or terrorists have an opportunity to ratchet up their level of destruction to previously unimagined levels. This is not a time for wishful thinking; this is a time for preparation for immediate action. There as a Boeing 777 at large, and very possibly it is in flyable condition and in the hands of terrorists. Do we as a peace-loving people have the foresight and will to actively shoot down an airliner when it re-appears? It won’t take to the sky again with innocent intentions. That is my worst fear, and I wrote this hypothesis with the hope of preventing it from becoming reality. Maybe I’m wrong, but if I am right, can we afford to wait and see? At the bare minimum, we should be on high alert until that aircraft is found—either intact, or in pieces as a result of a tragedy other than this hijacking scenario.

As I drag my overstuffed rollaboard and piggy-backing worn-leather flight kit down the fluorescent-lit Jetway, this chute is often stuffed with people waiting to board. I greet the cue with a joke to encourage them to politely let me pass by: “Excuse me please, I promise that I won’t take your seat. I have my own that has both a forward-facing window and access to an aisle.”

As I drag my overstuffed rollaboard and piggy-backing worn-leather flight kit down the fluorescent-lit Jetway, this chute is often stuffed with people waiting to board. I greet the cue with a joke to encourage them to politely let me pass by: “Excuse me please, I promise that I won’t take your seat. I have my own that has both a forward-facing window and access to an aisle.”

I spent most of my thirties deliberately wandering around the world—literally, all the way around. My fiancée Susanne had died onboard TWA Flight 800 before my 31st birthday when her Boeing 747 exploded. The last I ever heard from her is a call I missed, recorded on our answering machine. Her final words were mostly a reminder about radon tests we were conducting to complete our housing inspections. It’s a tape I play once every year to hear her voice again. She’s in the first class lounge enjoying a glass of wine, eating shrimp, and waiting for her flight to board—TWA Flight 800. It’s a flight that took off but didn’t land. The Boeing 747 blew up on July 17, 1996, at 2031lt .

I spent most of my thirties deliberately wandering around the world—literally, all the way around. My fiancée Susanne had died onboard TWA Flight 800 before my 31st birthday when her Boeing 747 exploded. The last I ever heard from her is a call I missed, recorded on our answering machine. Her final words were mostly a reminder about radon tests we were conducting to complete our housing inspections. It’s a tape I play once every year to hear her voice again. She’s in the first class lounge enjoying a glass of wine, eating shrimp, and waiting for her flight to board—TWA Flight 800. It’s a flight that took off but didn’t land. The Boeing 747 blew up on July 17, 1996, at 2031lt .

Strangers quickly become friends when our collective survival instincts are awakened. Our party grew as we reached our final days on the trail. The English chaps loved to haggle with the Tibetan refugee craft ladies, and they were buying up trinkets to decorate their new London flat.

Strangers quickly become friends when our collective survival instincts are awakened. Our party grew as we reached our final days on the trail. The English chaps loved to haggle with the Tibetan refugee craft ladies, and they were buying up trinkets to decorate their new London flat. As much as I love the mountains, the ocean is my true calling. I grew up in Connecticut near the shore of Long Island Sound. My eventual retirement dreams include a beach and a variety of seafood. As my new fiancée Alison and I work toward that dream, she insisted I take her to my favorite vacation destination, and last summer we sailed with friends on a pair of catamarans around the Greek Isles. Our deck holds were stuffed with bottles of Alfa (a Greek beer), fresh vegetables from the seaside market, and an abundance of feta cheese. We would save our seafood requests for each island’s local restaurants and often dine on the catch of the day that was literally caught only hours before. Mostly we explored Ithaca—the legendary home of Homer’s hero Odysseus. Alison summed up our excursion best on the back of postcards: ‘We’re following Odysseus’ trail, if in fact Odysseus was searching for fried calamari and gelato.’

As much as I love the mountains, the ocean is my true calling. I grew up in Connecticut near the shore of Long Island Sound. My eventual retirement dreams include a beach and a variety of seafood. As my new fiancée Alison and I work toward that dream, she insisted I take her to my favorite vacation destination, and last summer we sailed with friends on a pair of catamarans around the Greek Isles. Our deck holds were stuffed with bottles of Alfa (a Greek beer), fresh vegetables from the seaside market, and an abundance of feta cheese. We would save our seafood requests for each island’s local restaurants and often dine on the catch of the day that was literally caught only hours before. Mostly we explored Ithaca—the legendary home of Homer’s hero Odysseus. Alison summed up our excursion best on the back of postcards: ‘We’re following Odysseus’ trail, if in fact Odysseus was searching for fried calamari and gelato.’  If you’d like to read more about Alison’s and my Greek Island adventure, my article “Like the Wind” (with the online companion song of the same name, co-written and recorded by Das Binky) is in the current March issue of Airways that will be on the shelf at bookstores during the month of February. It is my 20th contribution to Airways magazine where I am both a writer and an editor.

If you’d like to read more about Alison’s and my Greek Island adventure, my article “Like the Wind” (with the online companion song of the same name, co-written and recorded by Das Binky) is in the current March issue of Airways that will be on the shelf at bookstores during the month of February. It is my 20th contribution to Airways magazine where I am both a writer and an editor. My memoir

My memoir